8.5 °c Wind speed: 10 km/h Precipitation: 9 % Cloudiness: 82 % Humidity: 78 mm Pressure: 9 mb

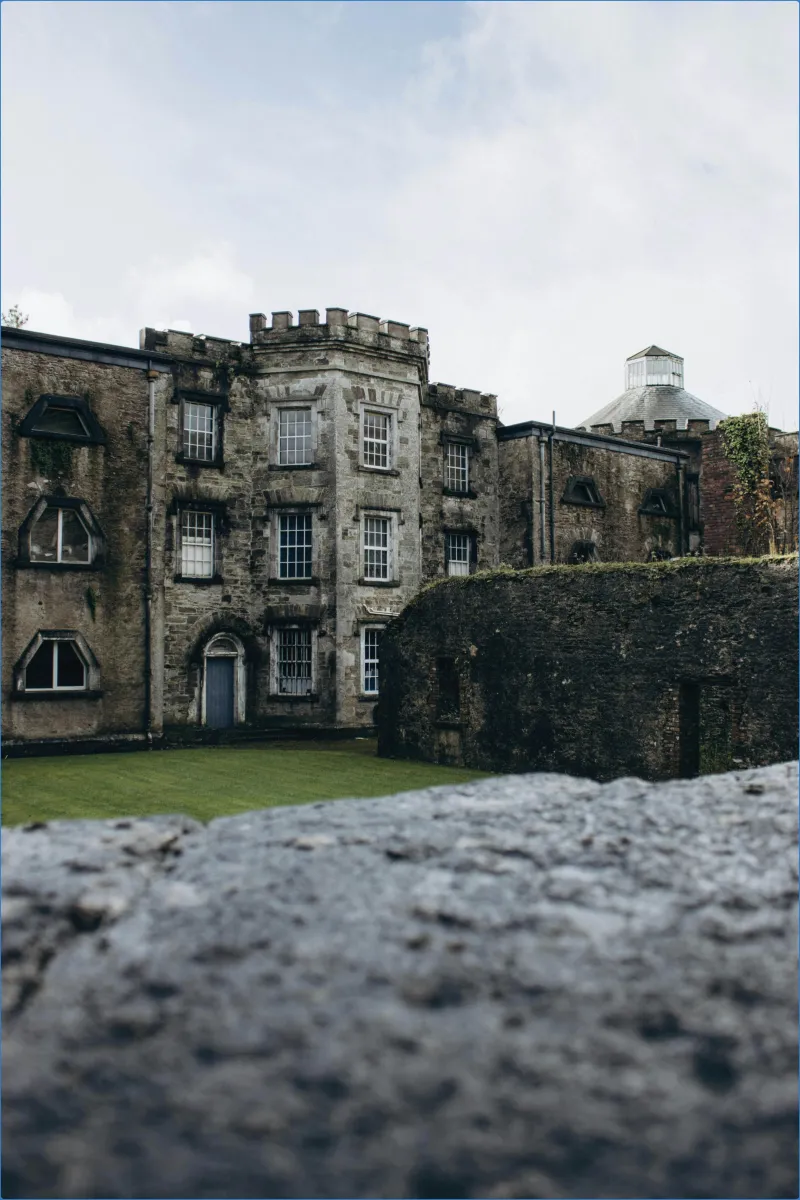

Kilmainham Gaol Museum

Murray's Cottages 12

Dublin 10

D

D10 VP98

Ireland

Description

Given its historical significance, the Kilmainham Gaol is a great place to include in a travel wishlist while in Dublin.

Dark past of Gaol

The end of the 18th century is marked by raising general concerns over awful conditions and much-needed improvements in jails as well as launching campaigns against the death penalty. A new gaol on Gallows Hill was designed by the architect John Trail. In 1796, the Kilmainham Gaol started to be housed after a decade of costly construction work (£22,000). Newly built premises and two wings of sixty-nine prison cells aimed to replace a local dungeon in close proximity to the site; however, not much changed in terms of detention conditions compared to the replaced prison. It still greatly depended on the gender and status of the inmates. The issues of overcrowding, poor hygiene and health problems remained unresolved as well.

The cells lacked natural light and heat, forcing the prisoner population to stay in darkness and coldness. The only source of artificial light and heat were candles in limited numbers. The gaslight lamps were installed inside the building only in the middle of the nineteenth century. Due to the absence of segregation, female and male prisoners of all ages were kept together in mixed cells until 1861, when the East Wing was redesigned for men. The Stonebreakers’ Yard received its name as it was a site where sentenced men broke up stones without any instruments.

During the extreme hunger periods, getting into gaol was still a way out to survive. People considered the prison to be a place where they could get at least a small amount of meals on a regular basis. With that in mind, they had to commit crimes, and they did. Taking into account the small size of a jail cell, which would accommodate one prisoner at a time, this led to jail overcrowding. Consequently, another problem in the form of various diseases occurred. The principal reason, though not obvious, for overcrowding was logistics issues. Four thousand imprisoned men and women were given a sentence of transportation to colonies in Australia. Given that, the gaol served as a "transit point" for those who awaited to be processed.

At the end of the 19th century, the government decided to close the gaol to save money. The jail became economically unprofitable since the number of prisoners had decreased greatly by that time. From 1911, the British Army utilized the Kilmainham Gaol for its military purposes. During World War I, it was used as a place of detention for servicemen. From 1916-1924, the gaol housed prisoners convicted for only political crimes. With the coming to power of the Irish Free State government, the prison stopped functioning in 1924. The gaol was regarded as a place of oppression and suffering by the Irish Nationalists.

Among the numerous criminals convicted for petty theft and/or murders were prisoners accused of political crimes. The majority of political prisoners were arrested for conducting revolutionary activity in their home country. They were determined to fight against British rule during the revolutionary period in Ireland. Henry Joy McCracken and Robert Emmet, the leaders of the United Irishmen, were at the top of the political prisoners list. They led the Rebellion of 1798 and the 1803 Irish Rebellion, respectively. In May 1916, the walls of the Kilmainham Gaol witnessed the leaders and participators of the Easter Rising suffering execution in the Stonebreakers’ Yard. Among the executed were Patrick Pearse, Thomas Clarke and James Connolly. They were well-known freedom fighters who signed the Proclamation of the Republic in April 1916. Other Republican political activists arrested and executed included Seán Mac Diarmada, Thomas MacDonagh, Patrick Pearse, Éamonn Ceannt, James Connolly, and Joseph Plunkett, to name a few.

Current perspective

In April 1966, after years of discussions and reflections on restoration, the former prison finally became a public place. Thanks to the volunteer activity of the Kilmainham Jail Restoration Society (KJRS), the building received a second wind as a museum. It acts as a memorial site to the Irish path to independence. Over the course of time, the museum has continually evolved and thus attracted more and more visitors. Now it has over three hundred thousand people a year. The audience interested in exploring the prison's history and life enjoys the possibility of examining the front blocks and cells inside of the building, the yard, and the surrounding area. The railings and the remains of the gallows fixtures, constructed in the late 19th century, will surely grasp your attention.

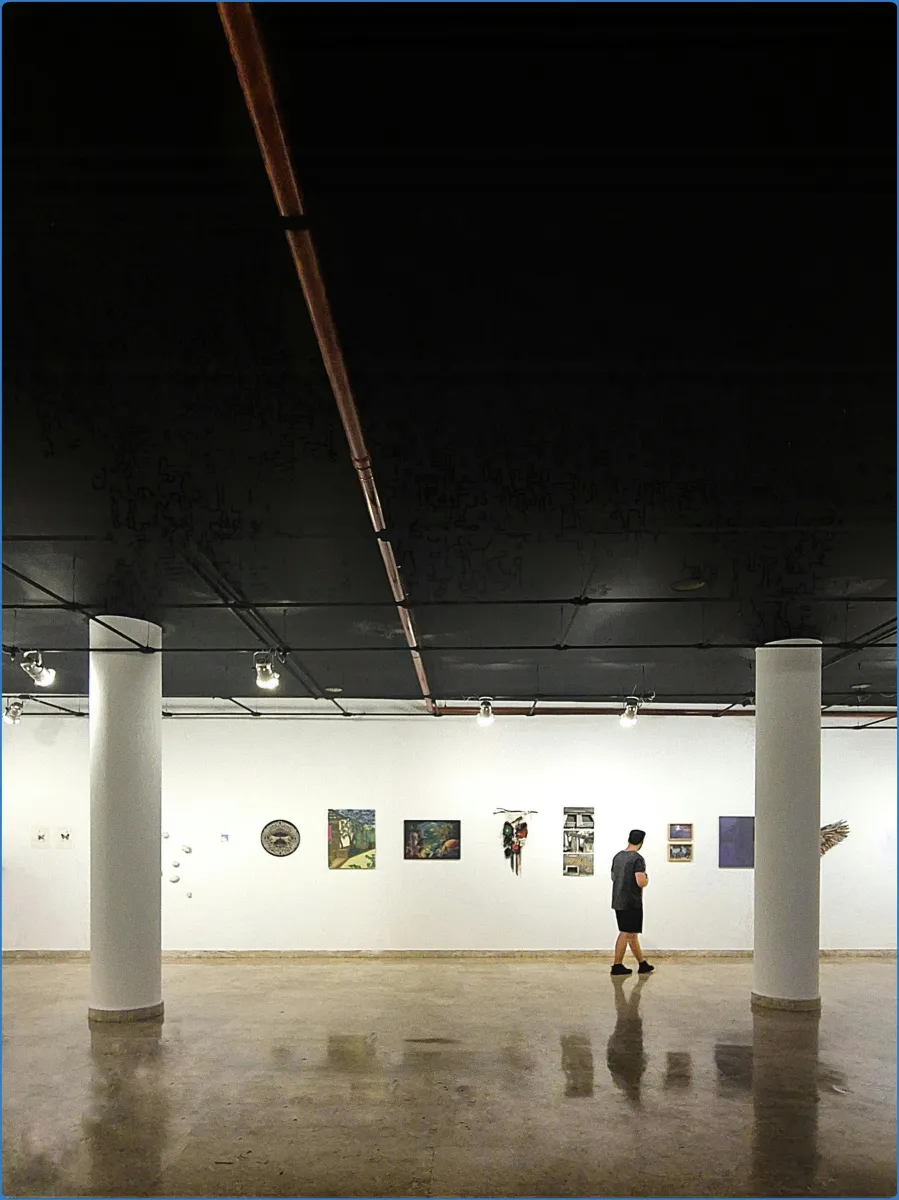

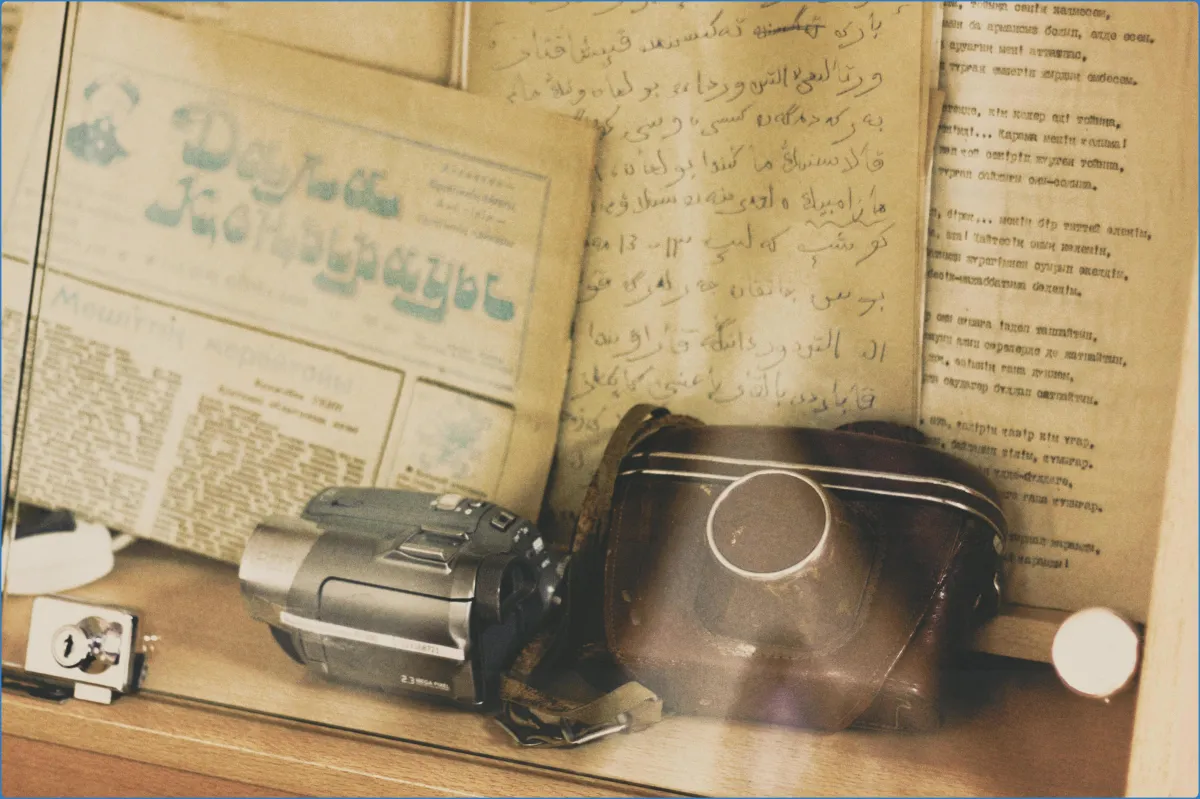

The museum contains a large exhibition space and regularly arranges temporary art exhibitions and various well-organized events for its visitors. The permanent exhibition is dedicated to the political history of Irish nationalism between 1796 and 1924. Objects donated to the museum by ordinary people include original copies of key Revolution-related documents, weaponry, and medals. Moreover, a collection of personal possessions which belongs to the leaders of the 1916 Rising has been put on display.

Kilmainham Gaol Museum encourages researchers and scientists to use the available resources and reserve collection, which is stored and cared for. Some of the documents can be accessed online by downloading them from the official page, and others by contacting the museum.

The prison that witnessed important events in Irish history reveals the dark pages of the past. Founded in 1796, it was a place of imprisonment for various political and social groups over the centuries. Today, the prison is used as a museum and is managed by the Office of Public Works, an Irish government agency.

FAQ

You can access the Kilmainham Gaol Museum only by taking a guided tour. If you plan to visit, make sure to book your tickets online in advance. The museum offers English- and Irish-speaking guided tours and leaflets with information in several languages.

The average time spent in the museum is around 1,5 hours.

Tickets for adults - €8, for seniors (60+) - €6, students and kids (12 to 17) - €4, and family tickets - €20.

Please take into account that the closest parking space is located at the Irish Museum of Modern Art.

No children under six years old are allowed.

Comments